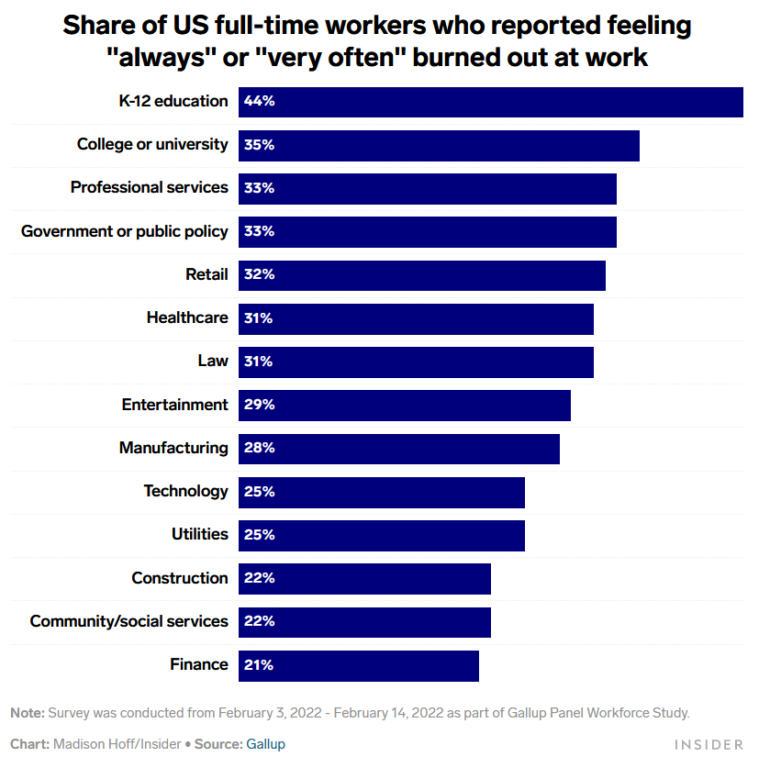

Every teacher has opinions about why the past two years have been much harder for teachers than previous years. Recent studies, including a February 2022 Gallup poll, show that teachers have the highest rates of burnout of any profession.

There are myriad causes of teacher burnout. Each one of us has our own experiences. Although the things that have made the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years so challenging for teachers are unique to each of our situations, there are several common factors.

Background (Prior to 2020)

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, teaching was becoming steadily more challenging. Most teachers are proficient at their jobs and do a reasonably good job of taking care of their students’ academic and general well-being in our classrooms. As with any grouping, there are always outliers, both good and bad. However, in the 1980s, outrage over the teachers who were ineffective and the students who failed to thrive gave rise to decades of educational reforms.

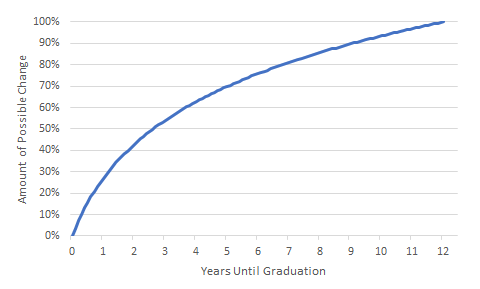

Pretty much every one of these reforms suffered from impatience. Most reforms had a timeline that more or less corresponded with our country’s four-year election cycle, despite the fact that a “generation” of students is the full 13 years from kindergarten through high school. Reforms have been presented as new standards for what students should be able to do at various checkpoints (usually as determined by standardized testing), but as far as I know, there have been no efforts to manage how to fill in differences between the path students had previously been required to follow and the new one. If a new set of standards is implemented, 13 separate pathways need to be defined:

- which of the gaps can be filled for 12th graders in their remaining one year of school, and how to fill them,

- which of the gaps can be filled for 11th graders in their remaining two years of school, and how to fill them,

- which of the gaps can be filled for 10th graders in their remaining three years of school, and how to fill them,

- and so on.

(Note: The graph depicts a logarithmic relationship. This is based on my own perceptions, and is not tied to any particular study.)

Obviously, the younger that students are when changes are implemented, the fewer accumulated differences there are between the old path and the new one, and the more time there is left to make up for them. However, if the changes are significant enough, adjustments need to be made to the requirements as well as the curriculum, which will need to vary over the entire 13 years of an academic generation. Unfortunately, these adjustments never actually get made, which means students and their teachers are continually expected to keep hitting a moving target with 100% accuracy.

Besides educational reforms and their attendant curriculum changes, there is also a continually increasing trend toward parents having less and less time and opportunity to teach their children the non-academic lessons that society believes they should know, and in many cases also less and less ability to provide for all of their children’s needs. Public schools in the US have always been expected to turn out students who are ready to take on the roles and responsibilities of adult life, filling the gaps between what they need and what their parents can provide. As those gaps widen, schools spend more time and resources on students’ non-academic needs. While this is absolutely necessary, it leaves less time and fewer resources for addressing their academic needs.

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Remote Learning

Most of us are aware of the problems that arose as a result of the societal shutdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Being stuck at home for over a year was traumatic for everyone. Students, families, teachers, and everyone else suffered from a lack of outside contact, and lived in a solitary echo chamber that amplified every thought. Because so much of our lives was focused on negative aspects of the pandemic—things we were no longer able to do, and how much harder it was to do those few things that we still could—most of us found ourselves repeating our frustrations inside and outside of our heads, and unwittingly projecting them onto others in our household.

In many cases, this resulted in increases in emotional and physical abuse. During the lockdown, I had many one-on-one Zoom conversations with students about their mental health, at whichever days and times they were available (including one Zoom meeting mid-afternoon on Christmas Day). In every one of these conversations, my students reported that all or nearly all of their interactions with their parents were critical and judgmental, which wreaked havoc on their self-confidence and sense of self-worth. Some of them spent the entire pandemic voluntarily incarcerated in their bedrooms, coming out only to use the bathroom and to get food for themselves.

As students spent more and more time in their rooms learning over Zoom while their mental health worsened, their ability to learn and make academic progress plummeted. Many students in Massachusetts who were remote from March 2020 until spring 2021 sank into depression and anxiety, and were able to complete less and less work as the 2020-21 school year progressed. Education pundits talked about “making up for learning loss” and “getting students caught up” while downplaying the mental health issues that were largely responsible.

Post-Lockdown: In Search of “Normal”

When students returned to the classroom in the spring of 2021, there was a lot of anxiety among teachers and students alike about COVID, which is still very much with us. However, there was also a level of euphoria about the return of in-person interaction. I recall walking through the halls during my prep period and listening to teachers telling students, “You’ve got this! I know you can do it!” With tears in my eyes, I realized that for so many of these students, this was one of their first positive, in-person interactions with an adult in over a year.

Unfortunately, those same education pundits who had told us for years that we could combat inequities by simply requiring our most vulnerable students to “have more grit” told us that we needed to “accelerate, not remediate,” and refused to relax any of the standards and requirements that had been in place pre-pandemic. This proved more difficult than anticipated, because students did not fully master the content of their 2020-21 classes but were compassionately given passing grades for those classes. This caused two significant problems:

- When a student receives a passing grade for a class, the student cannot re-take the class, even if the student has clearly not mastered the content.

- If a student received a passing grade for a class that is a prerequisite for another class, the student is expected to have the skills for the subsequent class. If the student did not master the content of the prerequisite class, the student will be unprepared to meet the requirements of the subsequent class.

This meant that students’ 2021-22 classes required students to apply skills that they never acquired. Students knew they were in over their heads, but teachers were ordered not to relax the requirements. Many students responded with a “fight, flight or freeze” response. Discipline issues this year are way up (“fight”), absenteeism is way up (“flight”), and more students than ever before resisted efforts from their teachers to get extra help or catch up on uncompleted work (“freeze”).

Administrators and state officials let the burden of dealing with these responses fall disproportionately onto teachers, many of whom who are also dealing with our own post-lockdown anxiety, trauma, and PTSD. When there are discipline issues, administrations require teachers to handle them in our classrooms, or they use PBIS and restorative justice as excuses to address the symptom in the moment but ignore the root cause. (How many of our students have learned that administrators will believe whatever they say as long as they sound sufficiently contrite?) When students are chronically absent, teachers are expected to use our already inadequate amount of prep time to call families (even if the teacher doesn’t speak the family’s home language). When students are unable to complete their work and end up failing our classes, teachers are blamed for not doing enough to get those students to pass. (Sometimes administrators retroactively change students’ grades to passing in order to enable them to graduate without having actually met the graduation requirements.)

As teachers are given more and more responsibilities beyond our students’ academic success, and as teachers are blamed more and more for problems that are well outside of our control, there is little wonder that nearly half of the profession “always” or “very often” feels burned out, and there is little wonder that more than half of teachers say that they are “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to leave the profession within the next two years.

I do not foresee any way that we can avoid at least a partial collapse of the current structure within the next 2-5 years. While there are privatizers (privateers?) who would welcome a total collapse of the public school system, there is no other system that is large enough, robust enough or responsive enough to fill the resulting void. This will probably result in a few years of large numbers of students being warehoused without making much academic progress. However, within about 5 years of the collapse and the chaos that seems inevitable, I believe that there will be a systematic overhaul of the profession and its demands. This overhaul will be forced to address the core issues that are now leading to the current collapse, and I believe that teaching can once again be a healthy and fulfilling profession as a result. My hope for the immediate future is that administrators and policymakers see the writing on the chalkboard (or white board or SMART board), and start addressing these issues sooner rather than later. The next generation depends on it.

Your diagnosis of “fight, flight, or freeze” hits the nail on the head. I was puzzled and frustrated as to why my students ( U. S. History, 11th graders) seemed to refuse to take advantage of the opportunities I presented for make -up work and extra credit.

We learned during distance learning that one teacher can post lessons and Zoom lessons that hundreds of students can access at once. I predict the future of education will include a few knowledgeable content experts and elearning specialists who manage the lessons for classes of hundreds, and then teachers assigned to a small cohort of students who will be responsible for in-person meetings with students and their families to provide individualized coaching, mentoring, and planning. Everything students need to learn is online. Education needs to adapt to change the role of a classroom teacher to either an elearning designer or a personal trainer (so to speak), not to try to maintain the unreasonable demands teachers face today of being everything to all students in every class they teach.

We more or less tried that model when the students returned to the classroom from distance learning. The buzzword is “blended learning”. Most of us learned that students are much less invested when they’re watching lessons, whether it’s in a Zoom meeting with their teacher on the other end or a knowledgeable content expert. This means that even when they do have an expert at the other end of the Zoom link, they get much less out of the lesson.