As you may or may not know, the etymology of the word “sophomore” is “wise fool”. The term is usually used for second-year students in high school or college because they often know enough to understand how the system works on a basic level, but are not aware of how much they don’t really understand. The term “fool” is appropriate, because fools tend to be inexperienced and naïve, but not stupid.

High school and (undergraduate) college happen in four-year increments. Freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior years are each one-fourth of the total experience. Freshman year is about learning and managing being a student in the school. Sophomore year is when students have mastered the freshman tasks and often try to show the freshmen how to do everything, even things they barely know themselves. Junior year is a time of gaining a deeper understanding and applying it to everything they learned to date, and senior year is a time of refining that understanding and preparing for the next phase, be it college or the workforce or a job or graduate school.

The problem with wise fools is that they have a high level of confidence, but usually cannot fathom just how little they actually understand. In a quote that is a popular paraphrase from Aristotle’s Metaphysics, “The more you know, the more you realize you don’t know.”

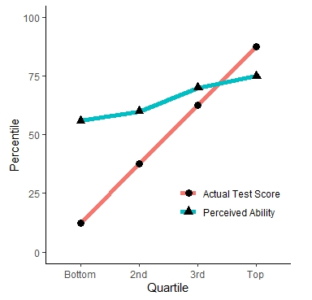

David Dunning and Justin Kruger studied this phenomenon and published the results in several papers, starting in 1999. The phenomenon is known as the Dunning-Kruger effect:

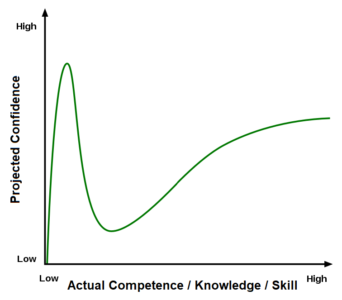

The Dunning-Kruger effect is more often portrayed in a graph like the following:

In the above graph, the confidence projected by those “wise fools” is represented by the tall peak near the left side of the graph. As people come to understand more about the competence/knowledge/skills required for the task, their confidence first dips (as it dawns on them how much more there is to know), and then gradually recovers.

Professions go through similar phases, though the increments are usually longer than one year. A teaching career is typically 20-30 years. While the timing of the phases varies from person to person, thinking of each phase as approximately five years seems to match what I have seen in myself and others. This means that a teacher with 0-5 years of experience could be thought of as analogous to a freshman, a teacher with 5-10 years would be analogous to a sophomore, and so on.

It is interesting to note that educators who become career administrators usually do so after just a few years of teaching. Those who make the switch during the “freshman” period are often unsuccessful, which is why most administrators seem to move to administrative jobs after 5-10 years in the classroom. (In fact, most administrator job postings typically ask for 5 years of classroom experience.) This puts a majority of them in the “wise fool” phase.

I do not mean this post to denigrate administrators. I have worked for some fine administrators who made the switch during their “sophomore” phase of teaching, and grew into their new roles phenomenally well. However, there are many administrators, especially those early in their administrative careers, who struggle to manage teachers who have more classroom experience than they do. They are much more likely to pounce on buzzwords and edu-fads. They are often afraid of anything that doesn’t have a rule or policy attached to it and many of them to over-prescribe processes and procedures, because this is the phase of their classroom management journey that they were in as “sophomore” teachers. They often focus professional development on the needs of new teachers, because their focus when they were in the classroom was on helping the “freshmen” teachers. These “sophomore” teachers-turned-administrators often lack the perspective to understand what would be useful for 15- and 20-year veterans.

At the building level, most administrators learn a lot in their first few years. If there are enough 15- and 20-year veterans in a school and the administrator is receptive and reflective, those veterans can nudge the school culture in the direction it needs to go. If the administrator fails at a task, some of these veteran teachers will pick them up, help them reflect on what happened, and help them make the appropriate adjustments. The astute administrator thus gains a deeper understanding of the needs of the school, and the task of managing it. However, if there are too few veteran teachers or if the administrator is not receptive to feedback, a toxic school culture can—and often does—result.

The bigger and more unfortunate problem is that there are more and more of these “sophomore” teachers moving into higher levels of administration, particularly at the state and national level. This is a dangerous trend, because as state-level administrators, they are no longer working among veterans who can help them get up and dust themselves off when they fail. In some states, administrators either have no classroom experience at all, or they made the switch during the “freshman” phase. When this happens, the administrators understand dangerously little of what they are managing, and they rarely have the experience to understand or learn from their mistakes, which makes effective change impossible. Many of these mistakes make the jobs of veteran teachers much more difficult or impossible, which is forcing many of those veteran teachers into retirement.

As the profession loses more and more of its veterans, the problem will likely continue to worsen in a downward spiral that has already damaged the most recent generation of students, and threatens to wreak havoc on the next. If we do not find a way to solve this problem, we will likely find ourselves careening into a dystopia in which the graduates of our education system are unable to maintain the innovations of previous generations. And there will be no teachers left to blame.

My experience with administrators parallels yours. I taught high school Spanish and French for 38 years, and I also concurrently taught at junior college. So many became administrators to escape the pressures and demands of teaching, while also earning much higher pay. Even if one is not an administrator, if one is out of the classroom for five years, in my experience, the general nature of students has changed quite a bit and one has to start as a freshman to learn about those changes; one still will be able to rely on teaching background. I taught in five districts and 10 schools, because sometimes I taught a split assignment between schools. My impressions were the same at each.